Collect to change the world

As collectors know, art has the power to change minds. Its spell can be overt or subliminal, drawing us towards new ways of thinking about and living in the world. Every year, the home of Art & Collectors – Gertrude Street – comes alive with Midsumma, Melbourne’s annual pride festival. Over in New South Wales, Mardi Gras ignites the city.

Moments like Midsumma and Mardi Gras are vibrant reminders of the role culture plays in progress. As stewards of visual culture, collectors play a role too. Perhaps social consciousness at the forefront of your collecting philosophy, maybe not. Either way, collecting values – first is worth bearing in mind – a reminder that what we hang ourselves on the wall.

Philippe Le Miere, 'pride gay rainbow flag'

Collect with Pride

The relationship between LGBTQIA+ history and art is rich. Without a history book, Queer artists use art to write their own story.

In her work, Rona Green draws on Queer aesthetics. Her cats are butchy: motorcyclists with tattoos. Or campy: opera attendees with capes cutting sharp silhouettes. These characters are never objectified; they look intently at the viewer, challenging us to stereotype them.

Queer artists also use their practice to deepen and problematize our understanding of identity. In 1999, descendent of the G’ua G’ua and Meriam Mer peoples, Clinton Nain (formerly Naina) began his ‘White King, Blak Queen’ series which explored colonisation through a vital black feminine perspective. It was an affront to white patriarchal dominance.

For a 2001 exhibition that utilised bleach on fabric, Nain’s brother John Harding wrote:

"The Blak Queen is omnipotent, knows no boundaries and recognises no colonising fences... Her splashes of bleach become evocative images of lingering memories, prodding us to remembered the truth."

Clinton Naina, 'I Look at the Skies'

Landscape Orientations

Landscape art is a prominent, near defining, tradition in Australian art. In capturing the splendour, breadth and diversity of the land, artists not only exercise their abilities but draw attention to the precarity of the environment.

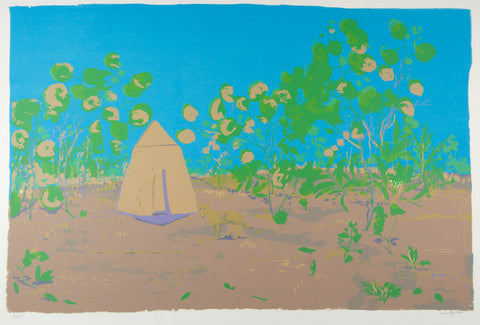

One artist invested in this is modernist Clifton Pugh. In 1954, Pugh travelled across the Nullarbor with his friend Noel Macainsh, realizing: “the boundless extent of a land, paradoxically both harsh and delicate, together with the illimitable space above it.”

Clifton Pugh, 'Presence of a Dingo'

This perception of the land as a vessel for time, humanity and spirituality came to underlie his art and environmentalism. Three years before visiting the Nullarbor, Pugh purchased land at Cottles Bridge: the eventual site of the artist’s community ‘Dunmoochin’. Instrumental in Australia’s conservation movement, the Dunmoochins worked to regenerate the land, witnessing first hand the degradation caused by feral animals.

Legally-blind artist, Erica Tandori's practice evokes the difference between sight and vision. For her, art is "safe place where I can see the world clearly, where there is beauty, colour, light and drama."

Open Invite

Art by women is just as varied as art by men. It doesn’t necessarily speak to the essence of “womanhood” or women’s issues, though it can. Rather, to invest in art by women is to recognize and celebrate the full spectrum of human experience, to move forward from a flawed history where many brilliant women were unjustly overlooked.

Whether socially engaged practice actually changes the world is difficult to discern. Despite this, it remains striking in its belief that art can be a force for betterment. Similarly, collectors don't need to forego art they love in favour of politics. Rather, social consciousness can be a lens through which you more fully grasp why certain images draw you in, move you, feel real and prescient.

"I think that art is the ability to show and tell what it means to be alive. It can powerfully visualize... your experience of the world, and there are a million ways to do it."